“Roger!” The History of Common Radio Phraseology

Humans have been using radios to communicate for over 130 years now. Ever since Guglielmo Marconi’s invention of the radio telegraph in 1894. From his humble beginnings designing his new radio in the attic of his Italian home to testing his invention by transmitting a signal over 2 kms a year later.

Today our limits of receiving signals is not one of signal strength, but of the physical limits of the planet we live on. For the VHF transmissions that are used in aviation today, it is the curvature of the earth that prevents us from sending signals to faraway places.

The formula that is burned into every pilot’s brain is:

d = 1.23 * (√h1 + √h2)

Here d is the distance in miles, and h1 and h2 are the height (in feet) of the transmitter and receiver respectively. This is a perfect solution to communicate to aircraft who can be five or ten thousand feet above the ground the air. Naturally, aircraft were one of the earliest users of “radiotelegraphy”: Using radio waves to send morse code.

Roger

In order to acknowledge receipt of a transmission by a station. The receiving station would transmit the morse code for the letter “R” (dot dash dot). This was much quicker and easier than sending the morse code for the entire word “received”.

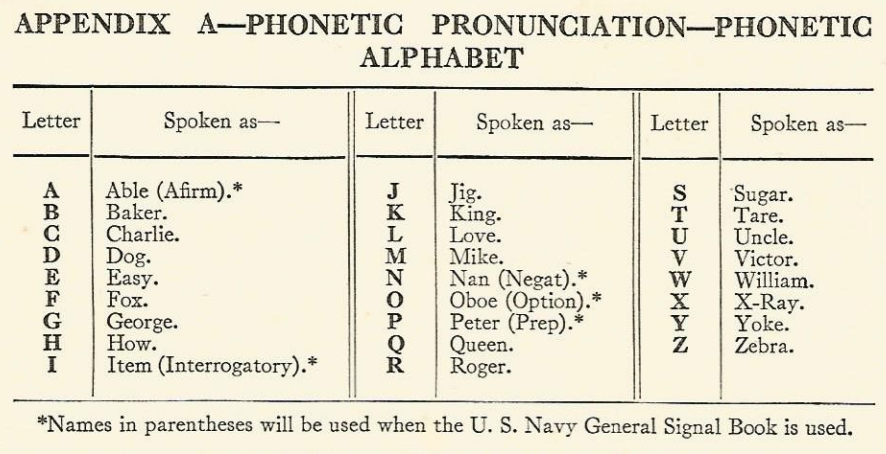

When voice communication over radio became more popular during World War II, the ICAO phonetic alphabet looked a little different. In 1947 ICAO created the phonetic alphabet from an existing alphabet that was in use by the US and UK during the war.

So, instead of sending the morse code for the letter “R” during voice communications, radio users would use the phonetic name for the letter “R” instead: “Roger”.

Since then, ICAO has updated the phonetic alphabet to be easier to read in other languages (such as French and Spanish). This included in renaming the letter “R” from “Roger” to “Romeo”. However the signal to send that you have received a transmission remained the same: “Roger”. Bonus points: there is never a need to say “roger that”, as simply saying “roger” implies that are talk about the previous transimssion.

Remember: the easier and quicker you can get your message across the radio, the more information you can receive.

Wilco

“Wilco” is a term that is used to tell the sender that you understand the transmission and that you will carry out the instruction. It is a concatenation of the two words “will comply”.

This is primarily used in aviation communication where a full read back of the instruction is not required, but you still want to let ATC know that you will comply with the instruction.

During the war most soldiers would say the full length “will comply” over the radio. Then over time it was shortened to “wilco”. ICAO made it part of its suite of standard phraseology around 1944.

Repeat / Say Again / Words Twice

Contrary to what you might see in the media and on film. The word “Repeat” is never used in radio communication. Mainly because it is too ambiguous. If you’re listening to a poor quality or broken transmission it may me hard to tell exactly what the transmitter wants you to do if you receive the word “repeat”.

This was determined to be the case during extensive testing of voice over radio communication in the 40s and 50s. As such, if the transmitter wants to repeat their transmission again, they will transmit “I say again”. A less often used way to repeat your transmission is using the phrase “words twice”.

Especially during very difficult communication “words twice” allows the sender to repeat words or blocks of words twice to ensure that the receiver gets the full message.

How Do You Read?

This harks back to the day of radiotelegraphy, where you would write down a morse code message. The question “How do you read” presumably literally means “are you able to read the message I just sent you on the piece of paper you wrote it down on”.

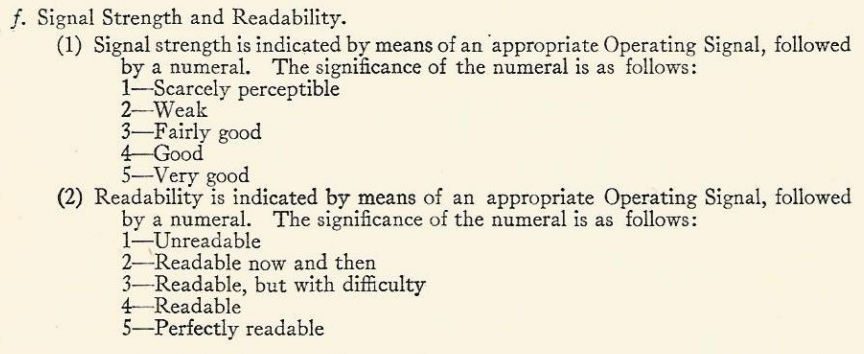

The reply would be two separate numbers on a scale of 1 to 5:

So a response of “five by five” means the signal strength is very good and your transmission was perfectly readable.

Mayday

Before the advent of voice over radio. The internationally recognized word or symbol used to require assistance was the morse code for SOS. Contrary to popular belief it does not mean “save our souls” or “save our ship”. The use of the morse for SOS (dot dot dot dash dash dash dot dot dot) was used because it was short, quick to transmit, and easily recognizable by radio operators.

Frederick Stanley Mockford, a senior radio officer at Croydon Airport in London, was tasked to find a similar word to be used for voice communication in 1923. At the time, most air traffic communications involved British and French pilots, making a phrase comprehensible in both English and French crucial. Therefore he came up with the word “mayday”, which is a French word (spelled m’aide), that translates to “help me”. The phonetic simplicity and distinctiveness of “mayday” made it effective for emergency use.

Pan Pan

“Pan Pan” is used in situations where urgency is still required, but it’s not as dire as a situation that would call for “mayday”. Once again the French language is to the rescue. “Panne” is a french word meaning “breakdown” or “mechanical failure”. It has been in use since the 1920s.

Conclusion

Radio communication is one of the many features of aviation that makes this form of travel the safest. In fact, the modern day list of standard phraseology has stemmed from some of worst aviation accidents in history.

The Tenerife disaster in 1977 is a good example of this. One of the main outcomes of this disaster was more strict rules around radio communication and standard phraseology. Such as:

- Replacing vague phrases like “We are at takeoff” with precise statements like “Cleared for takeoff” or “Ready for takeoff.”

- Prohibiting informal or non-standard phrases such as “OK” in critical communications.

- Prohibition of Similar Terms: Terms like “Takeoff” are now used only when clearance is given for the actual takeoff. Prior to clearance, terms like “departure” are used to avoid confusion.

- Mandatory Readback of Instructions: Pilots must read back all critical ATC instructions (e.g., clearances, taxi instructions, and hold short instructions) to confirm mutual understanding.

Including probably the most critical change to ICAO phraseology: Establishing English as the international standard language for aviation communication, with mandatory language proficiency requirements for pilots and controller.